Essay

by Marlene Lahmer

Through a seminar and a concurrent exhibition, I first came into contact with the logic of textile. There we discussed not only the material particularities of textiles but also the social patterns inscribed in the medium. Questions on gender ascriptions to the material, the value of women’s* work, and the hierarchy between art and craft resonated with me the most. Although I couldn't pinpoint at the time why exactly, I sensed that some textile-related ideas and principles would become important coordinators for my own artwork.

At the time, I had just returned from my Erasmus year studying glass art in Estonia — an experience that had confronted me with a special material-based knowledge and a new artistic tension field between my own body, technical skills, and glass idiosyncrasies. Hence I felt that my dealings with glass also equipped me well for a material-and-craft-governed discussion of textile art.

My friend Luzie and I discussed T’ai Smith’s essay “The Event of a Thread” (2015), a theory piece written as a tribute to Anni Albers and elaboration on her master-intertwiner-piece, the publication “On Weaving”(1965). Between us, we sent back and forth drafts on how to present the essay’s essence to our seminar group. Smith’s “Event of a Thread” emphasises a central quality of weaving: the possibility to move from every point in the woven structure to another and thereby trace non-linear and ‘non-gridular’ trajectories with the thread. She suggests to use this logic not only for textile creation but also to navigate through history, philosophy and art theory, to draw paths in time and space to form networks of meaning. Through the text, we learned to trace threads from Anni Albers’ work in 20th century Europe and America back to her pre-Columbian artistic ancestors, the Andean weavers who profoundly inspired her and whose legacy is said to be 8000 years old. We understood that, in weaving, threads can turn from weft into warp, from figure to ground, to any direction and back again (depending on the freedom a particular weaving device allows). Luzie, with a general affinity and access to quotidian magic, concluded: It must have been one thread all along. One thread that runs from obscure origins through millennia of textile production — as an undercurrent to its theorisation — and resurfaces in every work of textile ever made. It is, in essence, the same thread as those of 8000 years ago that has survived all the time to tell us its journey.

When I think of a thread as something that runs not only as a spatial but as a temporal continuity, I consider my grandmothers’ textile affiliations and wonder: Could it be the same thread that runs also through my family history? Does it draw yet unseen genealogies? Do I find my own artistic heritage in my grandmothers’ doings?[1] I am led to this conclusion because I realise the thread has emerged from my grandmothers’ time matrix and left us things as testimonies. Textile fabrications that were quotidian at the time seem more like practices of magic in hindsight. Objects flushed with post-war meaning were embedded in a nexus of causes and effects: boots made from a soldier’s coat, a smuggler’s dress with interior pockets and dishcloth sold by the metre.

Both my grandmothers grew up during the Second World War — or more accurately (I promise not to make this a war story) — the war intersected their growing-up. Both started their own families in post-war Austria which looked bleak both in the city and in the countryside, though in different ways. This is something I’ve been taught and told, though from my perspective it seems inevitable that the times of economic hardship and collective struggle wouldn’t last. Since I never felt the implications of war in my life, I find it hard to grasp the scope of what it meant to my grandparents, not only as an event but as a source of conditions that structured life.

There is this and other things I try to understand about my grandparents’ lives, but I repeatedly grasp at incomplete versions of the truth. For example, I grew up thinking that both of my grandmothers were housewives. This is true as most women with a household and no substantial wealth to afford domestic workers would have been considered housewives. This is accurate as both my grandmas would very much identify with the term “housewife” (likely more than with the labels of their various paid labour jobs). The issue is that for the longest time I didn’t know they’d had paid jobs at all. From today’s perspective — and with a winking eye at the sense of self-worth paid labour tends to instill in us — this biographical fact seems worth mentioning, and I feel like I’ve been somehow cheated on an important piece of information. Even for my grandmothers, paid work had a lot less to do with self-esteem than with financial necessity. Through this, I find out that the “general truth” of women staying at home in the olden days did not apply to my family nor to the working classes[2] they were part of. It is one thing to hear about women having to ask their husbands’ permission for working in paid jobs way into the 1970s in Austria, and another to realise this concept probably didn’t mean much to my grandmothers as they wouldn’t have come very far with only the men’s income.

Since my grandmother started working, a lot has changed in my family on the socio-economic scale, so that two generations later, equipped with a university background, I’m here writing to you about it in English, my second language. The way I relate to the term working class is mostly by participating in university discourses that conjure up the empowerment of the working classes in a theoretical realm. The degree to which this may be futile or patronising I leave to others to discuss, what I want to do here for the first time is follow the trajectory of class mobility in my own family history and arrive at the question: How do my grandmothers’ jobs, that I actually never knew about, relate to me being a student who is relatively carefree of economic struggle at the age of 24?

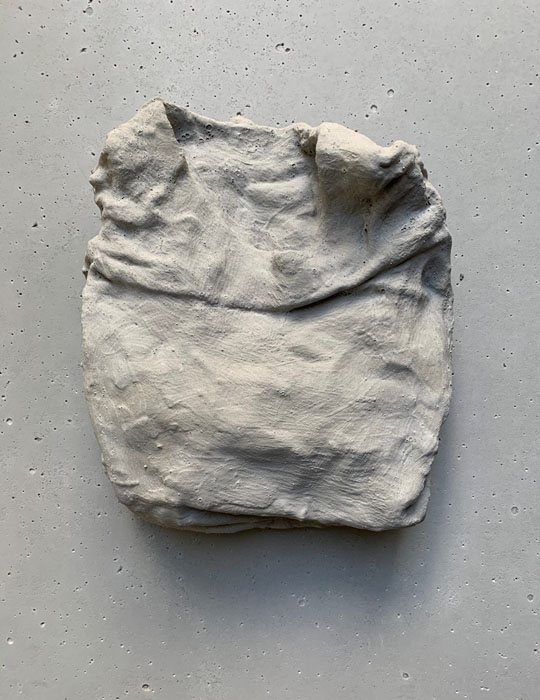

Both my grandmothers worked in textile branches at some points in their lives. One sewed bags on commission for a company in Vienna; the other worked at a wool dyeing factory in rural Lower Austria. What complicates this declaratory (somewhat celebratory) account of my grandmothers’ paid labour jobs is the unpaid but economically vital, often textile, work performed by women at home. Both my grandmothers also participated in this kind of economy. I know this because pieces of evidence — socks, scarfs, a bag — have survived in my wardrobe. Like many women at the time, my maternal grandma (who is still alive and tells me stories of her life when I ask) sewed, knitted, and crocheted clothes for herself and her children. Because fashion-wise there was “nothing to buy and no money to buy it with” as the famous quote in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) goes.

One of the first things that could be bought in Vienna after the Second World War — my grandma tells me — were dishcloths and handkerchiefs. You could buy them at the — presumably Russian, she remembers — markets, but you had to seam them at home because they were simply cut from a huge roll of fabric. In a way this means that whole districts were connected by one giant dishcloth cut to pieces. Cloth was one of the first goods available on the official market, at any rate. Better luck with finer ware, especially in the countryside[3], was to be found at the flourishing “Schleichhandel” (literally ‘creeping trade’, in plain language: black market). There was an elderly woman, known as “Oma” to my grandma’s family, who regularly came to exchange city commodities for supplies in eggs, fresh milk and the like. She went about her business in a wide flowing dress that had pockets sewn into the inside to hide the goods she was carrying. My grandma says she was a rather corpulent woman and with full bags she looked a bit more corpulent yet nothing out of the ordinary. In that dress she once brought white silk for my grandma’s communion dress, which the family had tailored so my grandma could wear the most extraordinary and beautiful dress at her First Communion. A thing like that hardly existed then and there.

Likewise another product of post-war economy and creativity was my grandmother’s blue and black boots that my drawing imagines back into being. They began their life as a soldier’s coat. Those coats could be found lying around anywhere after the war and my grandma’s family — like most people — collected them because they were good durable fabric, thick and warm. For the boot shafts they cut out the intact parts of one and re-dyed them dark blue. My grandma’s brother had a contact in Vienna who provided them with a piece of black leather that would become the shoe. They knew a skilled shoemaker who exceeded himself in putting the pieces together. Beyond the purely functional, the boots are said to have had straight lines of leather all the way up the front and back of the shaft as well as decorations in curved shapes that would hold the shaft and the shoe together.

If I shift my focus to these very pieces of fabric that found themselves a new dispositif in civilian attire, I come to share Anni Albers’ and T’ai Smith’s contention that textile is never “a single, stable object”, but that textiles survive as ever-changing meaning-makers precisely because of their “ability to adapt to new modes, new functional contexts”. Is this how concrete utopia is made in times of scarcity? I wonder. José Esteban Muñoz writes on utopia that we must turn to the past to find transformative energy for the future[4]. Undoubtedly, these soldier’s coats people found everywhere — war testimonies but more yet to… — were bursting with transformative energy, for they were thick and warm and made to survive (in). My grandma doesn’t have the boots anymore, but who knows where their material is today.

there once was a soldier coat

that would be shafts of boots

they cut out the intact parts

and re-dyed them dark blue

someone brought black leather

that would become the shoe

and the rest were decorations

to keep together shaft and shoe

***

[1] both of whom would have never associated the word “art” with the creative processes they were confronted with

[2] I refer to “working classes”, plural, to acknowledge the different social structures and distributions of work in urban and rural places. This seems relevant as my mother’s family lived in the city and my father’s in the countryside.

[3] where my grandma grew up and lived until she came to Vienna as a housekeeper at 18

[4] Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009)

* I use the asterisk to refer to the cultural concept of woman indicating an awareness that it does not necessarily coincide with biological gender. I would like to use “women*” not in terms of binary gender but to include all femme persons or all persons who are and were read as women. I find it important here not to make binary gender sound all too natural, even though or maybe exactly because it is often taken for granted when we talk about historical events.

Appeared in Issue Fall '21

Nationality: Austrian

First Language(s): German

Second Language(s):

English,

Estonian

Stadt Graz Kultur

Supported by: