Published January 31st, 2024

Review

by Zara Miller

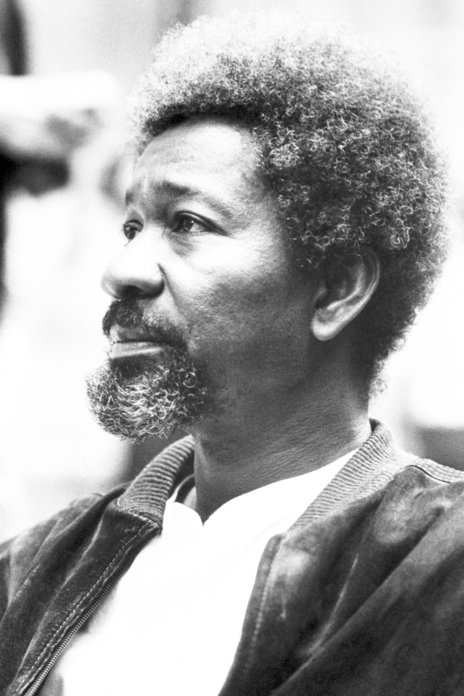

Wole Soyinka — 20th century Shakespeare from Nigeria — dictates the pace of transforming Africa’s socio-economic landscape in his award-winning play The Lion and the Jewel (1962). The first Sub-Saharan author to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, Soyinka’s life might not have been as eerily dramatic as Mandela’s — perhaps storytelling is a gentler playfield than politics — but the impact of his life’s work has echoed through the continents just as loudly.

The dry deadpan of the stances on social and economic relationships interwoven into Soyinka’s writing has a chip on its working-class shoulder. Soyinka spent a significant portion of his education in Leeds — the most working-class of all working-class towns in England — and while The Lion and the Jewel has been written before his immigration to the UK, the tug of war between the culture he was born into and the culture he adopted and clearly admires can be almost empirically traced in the play.

His writing is melancholic and yet celebratory, as it underlines the silliness of human discord in red but does not underestimate its nuclear power, as if he has lived one of his past lives in England and now tries to resolve the conflict between the love he has for the Western influence and the hate he can’t help but feel when looking at the state of dissolve it caused to traditional values in Nigeria. In The Lion and the Jewel, the Laureate sets up the ultimate battle between traditionalism and modernism and argues from both sides of the aisle.

Do not underestimate the power of differentiating views and the impact they have. There are no caricatures of British Colonialism or of the traditionalist ways of African culture. The story is poignant and draws attention to the two aforementioned topics without being too much on the nose. It does not advertise the message on billboards, yet it is unmistakably there. It possesses the crucial element, the ingredient that makes or breaks good storytelling, the salt of all stories — subtlety.

This is a work from the 60s, but it reads and feels like a piece from the 2020s. The time-traveling insight the playwright has, to deconstruct an entire geopolitical conflict between Nigeria and the UK, is nothing short of deep. And of course, because of that insight into modern audiences that transcends time, Soyinka knows no one wants to really read that stuff unless they sign up for it willingly under the sheet called Politics 101 (and even then, it was probably their dad who signed them up.) Therefore, Soyinka lays the changing geopolitical landscape of Nigeria under the influence of the British by juxtaposing it with a lover’s spat.

The main conflict is between Jewel and her two suitors. The dynamics of the interactions between the two suitors represent the hollow, dry bones of stubbornness. On one hand, we have a radical old-school leader who thinks that talent should be issued a one-time total payment of one hundred dollars for all the work they have done, are doing, and will ever do, and on the other a raging picketer who will not yield until he gets paid for every hour of his streaming hit-show.

Both men have valid arguments, while the woman between them is endlessly looking for someone who is the perfect mixture of their qualities — respect of tradition and open-mindedness to admit that times have changed. And those who do not adapt, die.

There is an argument to be made about the timelessness of literature: While some works age badly, The Lion and the Jewel does not belong to that group. It’s a non-preachy, three-dimensional conversation about societal expectations, gender roles, and how much freedom men and women have or don’t have when they are assigned these roles.

The clever use of the title suggests you are going to read one of Aesop’s fables. In a way, while the story is set in the village of Ilijunnle, Nigeria, the premise itself is quite fantastical — a conflict between clashing philosophies resolved in the span of a day. The three-act structure — in this case, morning, noon, and night — works like a charm. There is a reason chronological storytelling, simple (but not simplistic) Campbell’s hero’s journey, and an easy-to-follow plot are still in vogue.

While Soyinka might be Africa’s, or at the very least Nigeria’s, Shakespeare, the dialogue does not ask the reader to perform mental gymnastics — the play is very much a digestible meal even for those who don’t enjoy history or social commentary. All these factors are distilled into the several well-developed characters, three of which shape the story: Sidi, the village’s ‘Jewel’ as a symbol of a progressive modernization slightly if not entirely taking on the influence of the British in the area; Baroka, the ‘Lion’, the personification of Nigeria’s lore and heritage and the clan’s leader; Lakunle, the epitome of a westernized man.

The play thrives from a disease I like to call the ‘Anna Karenina syndrome’, i.e., how has this Russian countryside-raised, Marxist-infected old man managed to penetrate the heart of a young woman and take on her persona and struggles in such a human way? The same can be said here. Soyinka was still a young man when he wrote the play, not to mention he was raised in an environment so different from the West, yet the wholesome message of equality (some argue even feminism), and freedom of choice over one’s life is so femininely embodied in Sidi and so brilliantly juxtaposed in her suitor Baroka, that the play never steps on its own toes when imparting the message.

If you think this is some drivel, miserable story that drags its feet, you would be wrong. While the subject matter of choosing a husband, or rather, being forced to, is quite heavy, the characters achieve light-heartedness through humorous exchanges. The wit comes from a psychological concept called ‘shadow work’, which in literature means creating deep and profound characters by exploring their ‘dark side’. For example, the town Jewel Sidi is beautiful and when she realizes it, she turns into a Narcissus and annoys everyone, from her suitors to her friends.

On the other hand, Baroka is a hardcore traditionalist who resists the white man’s way and sticks to the inherited rules of the clan, so the reader would expect he is incapable of thinking on his feet, when in reality he is incredibly resourceful and saves his village from catastrophe several time with his imagination and creativity.

While the two men stand back-to-back measuring everything in all the ways the meaning of the phrase encompasses, they completely forget about the emotional and physical needs of the woman they supposedly care about. Yes, there is the staggering chasm that exists between them because they cannot agree on how life in Nigeria should be lived, and yes, they are both leaders of people in their respective rights — asking the ‘how’ question does not automatically mean ill-will. Yet when you reach the conclusion of the book, you stare at the wall and think back on the beginning, completely taken aback by the sheer stupidity and self-serving motivations of the characters. And when you do think back on it, you suddenly cannot remember why the two men were at each other’s throats in the first place when they are trying to reach the same goal — which I believe is the desired effect Soyinka was going for. For the audience to conclude that these two just randomly sniffed each other one morning and decided they didn’t like the smell.

It’s a classic take on the love triangle trope, with a dose of unhealthy selfishness in all three of the main characters. A surprisingly fun read well deserving of its accolades, a great satire of the human mind.

Nationality: Slovak

First Language(s): Slovak

Second Language(s):

Czech,

English,

Russian,

Spanish

Supported by: